Health care is a major polluter both in terms of emissions and contributions to landfills.

The combined health sectors of the United States, Australia, England, and Canada emit an estimated 748 million metric tons of greenhouse gases each year, more than all but the six top polluting countries in the world.

Meanwhile, a report on 110 Canadian hospitals published in 2019 found those institutions generated nearly 87 000 tons of waste annually — roughly the equivalent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which spans twice the area of Texas.

The COVID-19 pandemic exponentially increased the use of disposable medical supplies, with 3 million face masks used every minute globally, according to a 2020 estimate.

Yet, awareness of the health sector’s environmental impact is low, especially when it comes to the proper disposal of medical waste.

What waste goes where?

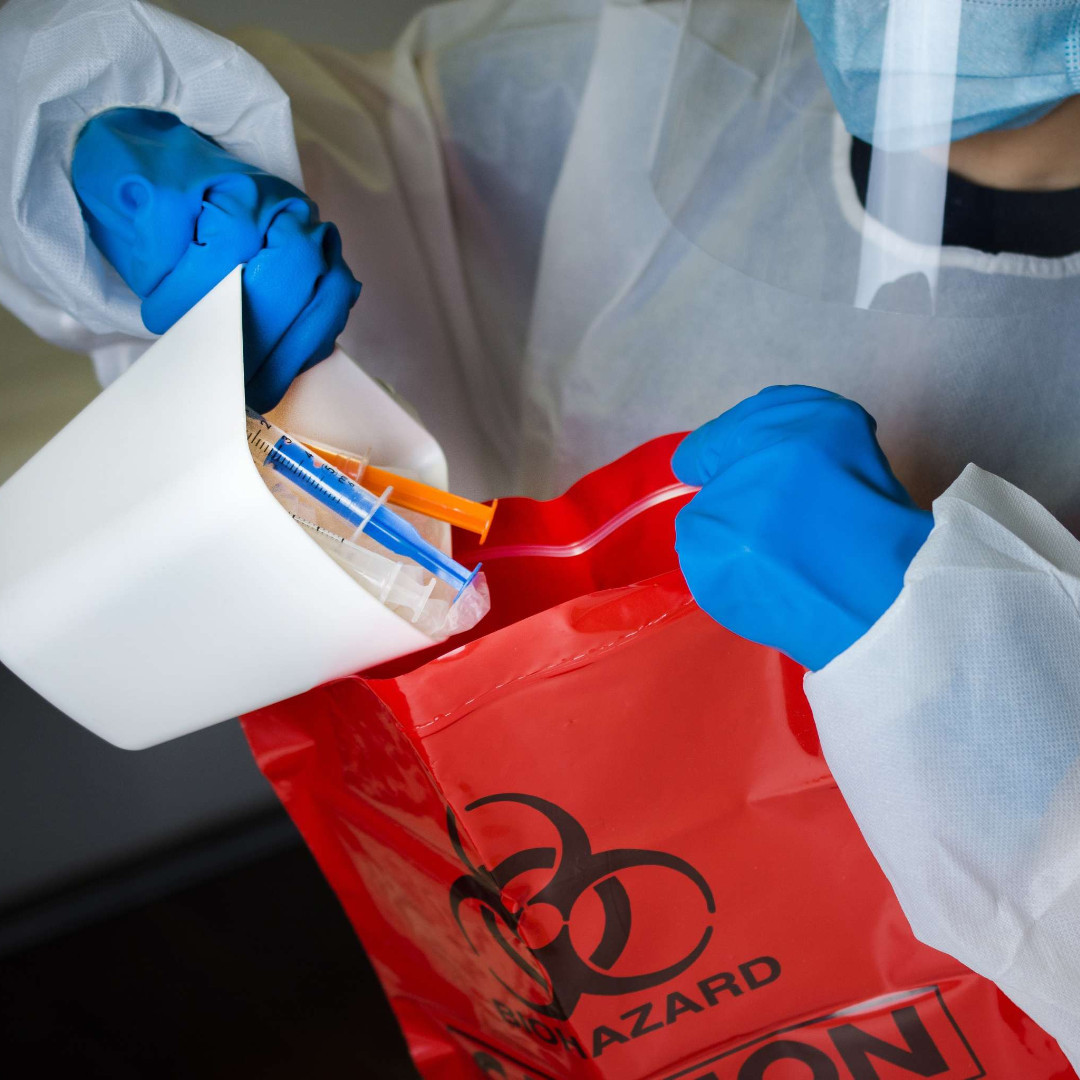

About 85% of hospital garbage is general, nonhazardous waste that can be recycled or sent to a landfill without any special processing. This includes items like dressing sponges, diapers and incontinence pads, personal protective equipment, disposable drapes, IV bags, tubing, catheters, lab coats, and pads that won’t release liquid or semi-liquid blood.

However, much of this general garbage is improperly discarded with hazardous waste and either incinerated or sanitized in an autoclave before heading to the landfill, according to Laurette Geldenhuys of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment (CAPE).

Even among members of Geldenhuys’ regional CAPE committee, many didn’t know what truly belonged in hazardous waste bins. “There seems to be a lack of knowledge out there,” she said.

Hidden costs of improper disposal

Unnecessary extra processing of general waste is more costly for health systems and the environment, Geldenhuys said. However, tracking these costs is difficult since Canada doesn’t consistently collect or report data on medical waste.

At the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, where Geldenhuys works as a nephropathologist, a large proportion of “special” hazardous waste is incinerated.

“Apart from the fact that Nova Scotia Health pays for it… [incinerating unnecessary items] significantly adds to the greenhouse gas emissions of the organization,” she explained. So, “the less special waste one can create, the better.”

Geldenhuys’ lab was able to reduce its special waste output by 75% within a month by conducting an audit, providing additional bins and bags for recycling and general garbage, and educating staff on what items go where.

Operating rooms driving waste

Operating rooms particularly present “tremendous” opportunities for waste reduction, said Syed Ali Akbar Abbass, an anesthesiologist and chief of environmental stewardship and sustainability at St. Joseph’s Health Centre in Toronto.

On average, operating rooms drive up to 60% of a hospital’s supply costs and produce more than 30% of a facility’s total waste and more than 60% of its specially regulated medical waste.

In a recent audit of disposal bins for “sharps” like needles, lancets and blades, Abbass found that up to 90% of the contents were inappropriate — including paper and plastic trash, metal instruments that weren’t sharp, and cutlery from the cafeteria.

“It boggles my mind as to the amount of waste,” he said. For example, “needle drivers aren’t sharp, they aren’t scissors, and they can’t cut anybody — they’re used to hold things. But they’re thrown in the sharps container because of poor understanding of waste segregation.”

Putting the wrong items in sharps containers constitutes a very expensive trip to the landfill, Abbass said. “It’s orders of magnitude more expensive [than throwing trash in the garbage] because it first gets sterilized by autoclave.”

He estimates hospitals could see “upwards of $100 000 in cost savings just by doing appropriate segregation of waste.”

Recycling initiatives taking off

Meanwhile, many items could be diverted from landfills entirely.

In 2018, Abbass initiated a reprocessing program for single-use medical devices used in St. Joseph’s operating rooms in partnership with the medical equipment company Stryker. Normally, these devices would have been thrown into the sharps container, autoclaved, and ended up in a landfill. But now, Stryker collects the items at no cost to the hospital and either refurbishes and resells them at a discount or recycles their raw materials.

In 2020 alone, the program diverted nearly half a ton of single-use biomedical device waste from landfills and saved the hospital thousands of dollars in both sharps waste and device costs.

St. Michael’s Hospital has since joined the program, and Abbass is searching for a metals recycler to reprocess other medical instruments.

Abbass also led St. Joseph’s to become the first facility in North America to recycle medical PVC — a flexible plastic used for IV fluid bags and oxygen masks. The hospital partnered with Norwich Plastics in 2016 to launch the program and has since secured federal funding to support other hospitals joining the initiative. Now, about 20 hospitals in Ontario are recycling medical PVC.

Beyond volunteer efforts

Abbass is developing a staff education module on waste reduction but said organizations need a dedicated sustainability director or manager with an institutional mandate to drive these initiatives.

It’s also important that sustainability efforts involve clinicians who may be able to spot waste overlooked by hospital administrators. For example, Abbass said, an administrator may not question if a vendor tells them that a plastic syringe with a needle should be discarded with sharps, but a clinician may push to discard the plastic part separately, knowing only the needle poses a hazard.

Currently, many of the clinicians involved in sustainability initiatives are volunteers, limiting the time and resources they can dedicate to the work.

Still, Abbass said, “I believe there’s a business case that a sustainability administrative position will pay for itself in the savings that position will provide.”

This content, Improper disposal of medical waste costs health systems and the environment, was originally shared by Canadian Medical Journal Association (CMJA) on April 11, 2023.