The industry is rarely mentioned among the chief planet polluters — and companies are intensifying their sustainability efforts to make sure it stays that way.

In August, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body of scientists convened by the United Nations, issued a long-anticipated report. You probably heard about it: Based on more than 14,000 studies and approved by the government of every U.N. member nation, the IPCC report is the most comprehensive summary to date on the science of climate change.

Chief among its findings was that humans have heated the planet by 1.1 degrees Celsius since the 19th century, and that even if emissions were sharply cut today, another 1.5 degrees of warming is likely already locked into the system. This would put a billion people around the world at risk of regular life-threatening heat waves. “Things are unfortunately likely to get worse than they are today,” one of the report’s authors told The New York Times.

That sounds bad and, well, it is. But the IPCC report essentially just confirmed, if in harrowing terms, what was already widely known about Earth’s climate. It also reiterated the possibility that humanity can still prevent even more catastrophic outcomes with a coordinated effort among nations and industries.

The pharmaceutical industry is rarely mentioned among the sectors most responsible for polluting the planet. Most of the blame — and thus most of the public pressure — is directed at energy, construction and transportation companies.

But big pharma should not be immune to criticism. In December 2018, two researchers at Ontario’s McMaster University found that not only is pharma a significant contributor to global warming, it’s actually dirtier than the automobile industry, emitting 13% more megatons of CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) despite being 28% smaller.

The study, which was published in the Journal of Cleaner Production, was the first peer-reviewed attempt to quantify pharma’s overall carbon footprint. Previous analyses had been narrower (one looked at pollution caused by drug manufacturing alone) or much broader (a 2009 report measured the environmental impact of the entire U.S. healthcare sector). Nonetheless, the McMaster study was damning of pharma’s climate impact, finding that the industry would need to reduce emissions intensity by 59% by 2025 in order to comply with the reduction targets set out in the Paris Agreement.

In order to make fair comparisons among companies of wildly different sizes, the McMaster researchers measured emissions intensity: metric tons of CO2e emitted per $1 million of revenue in 2015. They found that emissions intensity varied greatly between companies, regardless of their size.

For example, Eli Lilly emitted 5.5 times more CO2e per million than Roche. Procter & Gamble’s emissions were five times greater than Johnson & Johnson’s, even though the two companies generated the same level of revenue and sell similar lines of products.

That variability contains a hopeful truth. It is possible, right now, for pharma companies to do better when it comes to sustainability.

Indeed, while the industry as a whole is far away from meeting the Paris targets, some of the largest companies were already in voluntary compliance with them in 2015, including Amgen, Johnson & Johnson and Roche. What’s more, those three companies were also the ones with the highest level of profitability and revenue growth in the whole sector. Roche, Johnson & Johnson and Amgen showed revenue increases of 27.2%, 25.7% and 7.8%, respectively, between 2012 and 2015, while managing to reduce their emissions by 18.7%, 8.3% and 8.0%.

In other words, sustainability and growth aren’t mutually exclusive. As Lotfi Belkhir, one of the McMaster report’s authors, wrote in an article summarizing the findings: “If those performance levels are achievable by some, why can’t they be achieved by all?”

One major problem is that current guidelines for reporting environmental impact are voluntary and unstandardized. Of the 200-plus pharma companies McMaster University analyzed for its report, only 25 of them reported their 2015 emissions.

But in recent years, as biopharma companies seek to shore up their bona fides as responsible corporate citizens, there has been some progress on the sustainability front. Sanofi recently joined RE100, a global initiative in which companies commit to 100% renewable energy by 2050 (in France, all of Sanofi’s sites are already fully renewable-powered).

Early last year, AstraZeneca unveiled its “Ambition Zero Carbon” strategy, which aims to eliminate emissions from its global operations by 2025 and to be carbon neutral across its entire supply chain by 2030. And in June, AbbVie became the latest large pharma company to commit to the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), which sets emissions targets in line with the Paris Agreement. Of the 26 pharma, biotech and life sciences companies with firm SBTi commitments, 14 have signed on this year alone, including Pfizer, Charles River Laboratories and Illumina.

And then there’s Novo Nordisk, which committed to SBTi in 2018. With its Circular for Zero initiative, the Danish multinational pharma giant aims to zero out emissions from its global operations, including its supply chain, by 2030.

Circular for Zero is far from the company’s first environmental push, according to Katrine DiBona, corporate VP of global public affairs and sustainability. “It goes back 20 years, starting with windmills in Denmark and turning off the lights,” she says. “We’re on a completely different scale now.”

DiBona leads a team of 65 colleagues in developing sustainable business strategies, conducting data and trend analysis and mobilizing internal and external stakeholders. The company’s environmental platform has several pillars, from emissions, water and energy consumption and waste management to travel and distribution. Last year, it became the first pharma company in the RE100 initiative to have 100% green power at every one of its production sites across the world. The company got there using a combination of solutions, including solar in the U.S., biomass fuel in France and, yes, wind power in Denmark.

To create true and meaningful change, DiBona says, pharma companies need to set clear and ambitious targets, integrate them into strategic aspirations and hold suppliers to account. More than 80% of Novo Nordisk’s emissions come from its supply chain, DiBona says, identifying that fact as a big reason the company last year said it would require its suppliers to use green power by 2030. Already 25% of emissions from Novo Nordisk’s direct suppliers are covered by renewable power commitments.

“We’re generating rings in the water,” DiBona says.

DiBona is particularly proud of the company’s progress with plastics. Every year, Novo Nordisk produces about 550 million plastic insulin pens, most of which end up in garbage cans. “When you look at our footprint, it’s a big part of it,” DiBona says.

To begin addressing this, last year the company piloted a take-back program. At pharmacies in three large cities in Denmark, patients picking up their medicine could return used plastic pens. The parts were then upcycled: Some were used to make office chairs in collaboration with a Danish design firm, while glass from the insulin vials was melted down to create lamps. DiBona says the take-back program will expand to other countries soon.

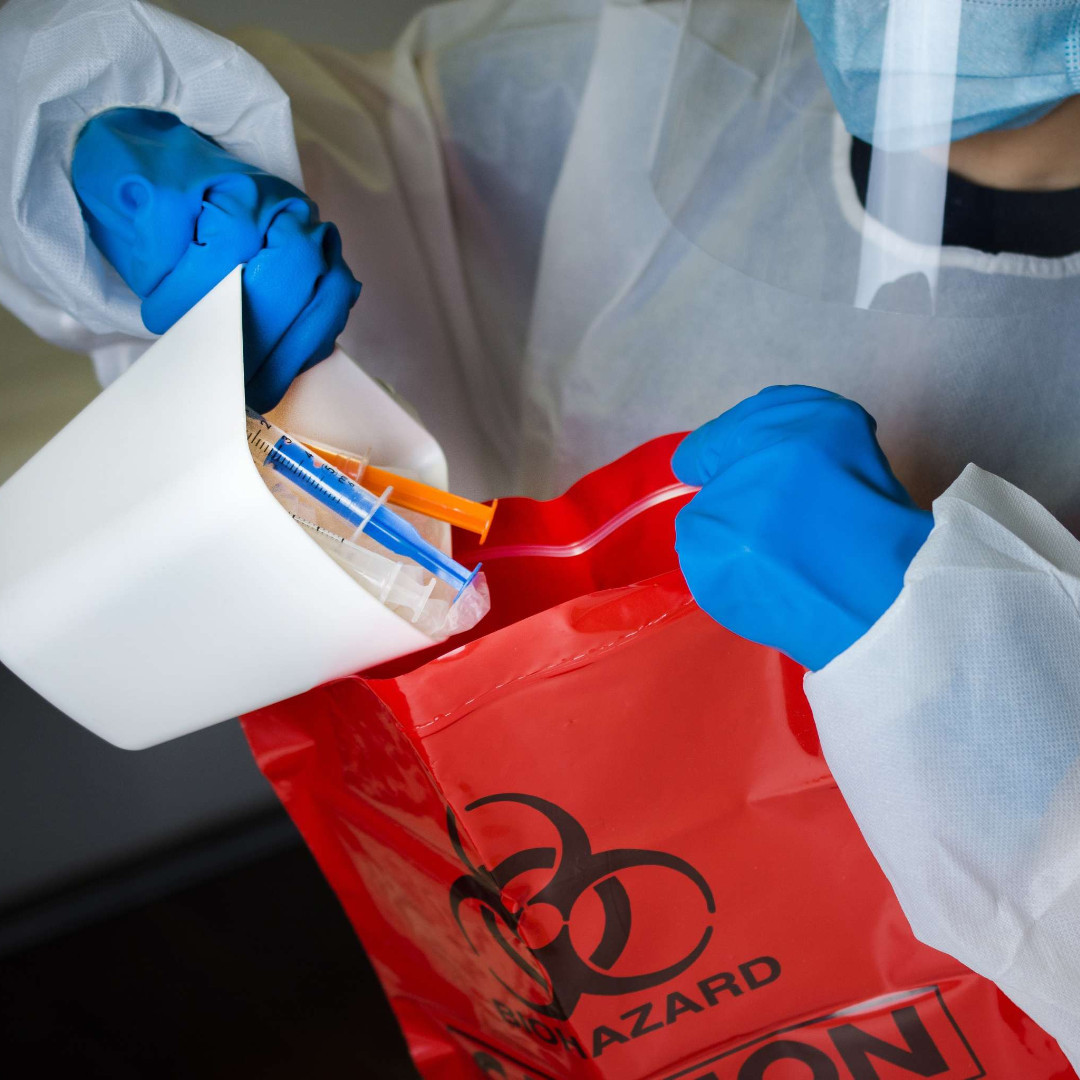

Another company trying to close the loop on plastic waste is Stericycle. The compliance company specializes in collecting and disposing of controlled substances, medical waste, biohazardous material and sharps. Through its Sharps Management Service, Stericycle provides reusable sharps containers to hospitals, pharmacies and clinics, then picks them up, cleans them in a high-temperature, high-pressure process and ships them back out. The containers can be used a couple hundred times.

Last year, the program diverted an estimated 104 million pounds of plastic from landfills, according to Stericycle’s latest corporate social responsibility report. In recent years, Stericycle has also brought in new leadership from large logistics companies to improve its routing efficiencies.

There’s an obvious, if often overlooked, benefit to this type of streamlining, and it goes back to the correlation between the greenest and highest-growth pharma companies in the McMaster University study. Improving sustainability is not just good for corporate image; it can also help the bottom line.

“Sustainability is about doing the right thing that makes the right business decision,” says Jennifer Koenig, VP of environmental, social and governance for Stericycle. “You can make lots of environmentally correct decisions, but if they cost so much that you can’t be profitable, that’s not sustainable.”

In a warming planet with more extreme weather, strengthening resiliency and efficiency throughout the corporate product chain will become more necessary. Just look back to 2017, when Pfizer’s manufacturing facilities in Puerto Rico were wiped out during a devastating hurricane season, resulting in a loss of an estimated $195 million in inventory.

For Novo Nordisk’s DiBona, the next phase of progress won’t truly begin until solutions are implemented industrywide.

“With the take-back program, we appreciate what we can do as one company with one brand of device,” she explains. “But if this were an industry solution — imagine how we could scale that to a much bigger degree?”

Eventually, sustainability will just be integrated into every strategy decision a company makes. New environmental initiatives will no longer be heralded by press releases; they’ll just be the way of doing business. “Progress” on this front is only measurable now because the pharma industry — all industries, really, and the species as a whole — is in the early phase of a profound shift, and the clock is ticking. The only question is how much agency they, and we, will have in determining what that looks like.

“It’s an interesting dynamic. By going for big impact, you can actually run the risk of being less visible,” DiBona says. “Maybe silence is actually a good sign. Let’s see if that’s how it turns out.”

From the November 01, 2021 Issue of MM+M – Medical Marketing and Media

This post, Pharma & Climate Change: How Can Companies Make Meaningful Contributions?, was first shared by Medical Marketing & Media (MM&M) on November 4, 2021.