Workplace safety inspectors are conducting nearly 200 coronavirus-related investigations to determine whether employers failed to adequately protect their workers, according to data from the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Half involve employee deaths or hospitalizations.

The inspections target nearly 50 hospitals and two dozen nursing homes, including one in Joliet, Illinois, where administrators believe an infected maintenance worker spread the virus room to room. Twenty-four residents died, along with a nursing assistant and the maintenance worker himself.

Also under review: a school system garage in Lexington, Kentucky, where 17 employees tested positive and one died; a meatpacking plant in Dakota City, Nebraska, where the widow of a deceased employee said he kept working after getting sick so he could get incentive pay; and two Native American schools in Arizona that reportedly stayed open after others shut down and where two employees died.

In all, OSHA officials are reviewing workplaces in two dozen states with a total of 96,000 employees, according to USA TODAY’s analysis.

OSHA has been under fire for not doing enough to protect workers amid the pandemic. State and federal OSHA offices have fielded thousands of coronavirus-related complaints since January, according to records released last week.

In recent weeks OSHA also has uploaded data detailing inspections that were launched by federal and state officials and refer to COVID-19. They reveal which inspections are being conducted at what companies.

A total of 192 COVID-19-related inspections were launched between Feb. 19 and April 23. Many were triggered by complaints that employees were in danger, had been hospitalized or died. Five cases have since been closed; the rest were open, according to data released Tuesday.

Unions say oversight of workplace safety is weak

Labor unions say the federal workplace safety agency isn’t doing enough. The AFL-CIO, which represents more than 12 million workers, sent a scathing letter Tuesday to Labor Secretary Eugene Scalia, who oversees OSHA, accusing the agency of being too lenient and slow.

“For all workers, the toll of COVID-19 infections and deaths is mounting and will increase even more rapidly as workers return to work without necessary safety and health protections,” AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka wrote in the letter, which listed dozens of members who have died from the virus.

He faulted the agency for not doing more inspections, notissuing citations and releasing only voluntary coronavirus safety guidelines. “Without government oversight and enforcement, too many employers are disregarding safety and health standards,” he wrote.

Under federal law, OSHA has jurisdiction over most workplaces in the country. It can issue regulations and enforce them with inspections, citations and legal actions.

Twenty-six states, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have their own OSHA offices that work under the authority of the federal agency. State workplace standards can’t be weaker than federal ones.

In a response to Trumka released by the Department of Labor on Thursday, Scalia disputed the union’s assertions and argued that when it comes to workplace safety, “the cop is on the beat.”

In a statement provided to USA TODAY, OSHA said it has been “acting to protect America’s workers by providing extensive guidance to employers and workers on COVID-19 response.” As of Wednesday, it said more than 200 COVID-related inspections have been launched.

OSHA declined to comment on specific inspections because the cases remain open. “The agency continues to field and respond to complaints, and will take the steps needed to address unsafe workplaces, including enforcement action, as warranted.”

A barrage of workplace safety complaints

Nearly 4,000 coronavirus-related complaints were filed with federal and state OSHA offices between Feb. 24 and April 6. OSHA withheld the names of employers and other details in about 3,100 because those cases are open.

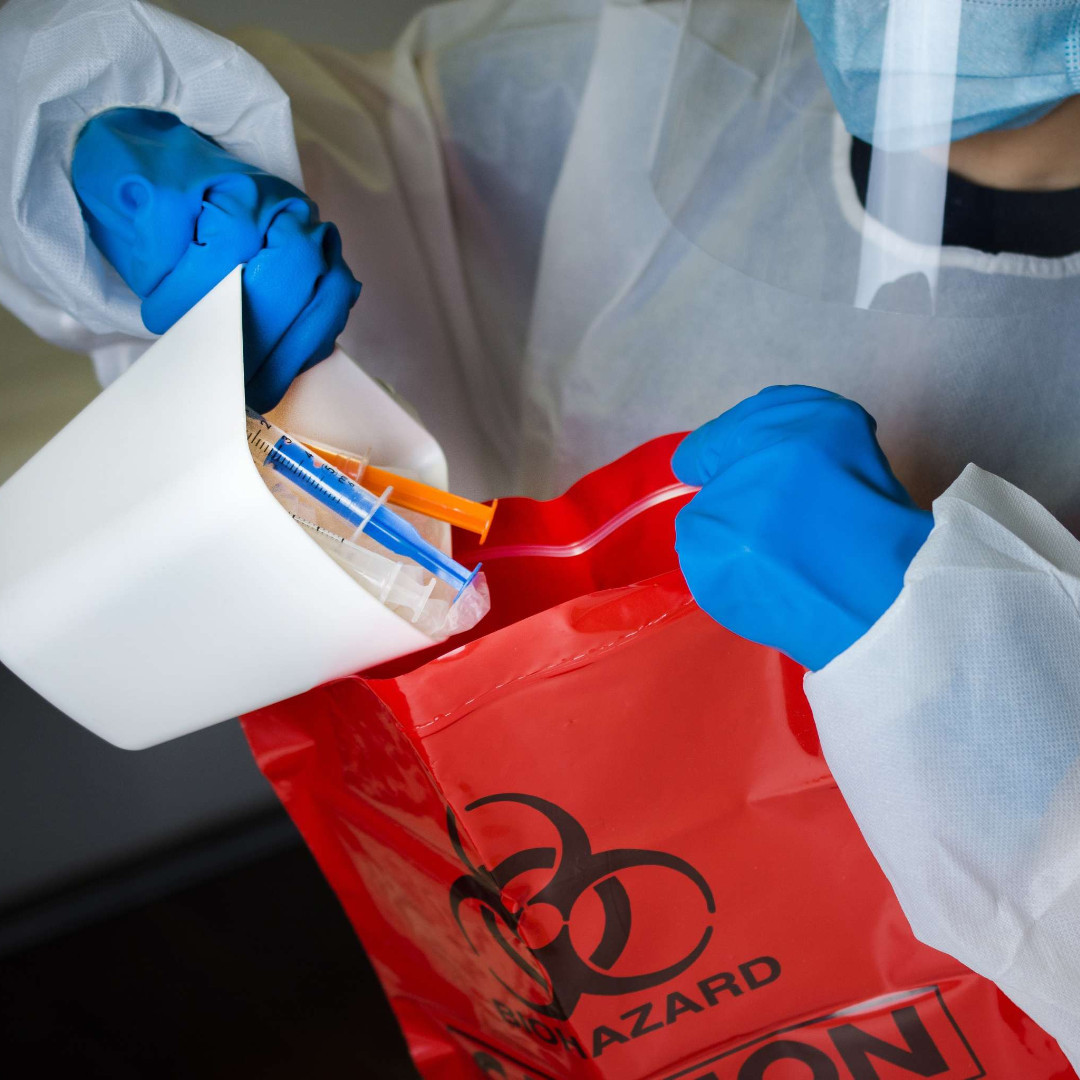

More than one in four complaints involved health care facilities, where problems included a lack of masks, respirators and other protective gear. Some complainants said employers didn’t notify staff when coworkers tested positive or allowed people suspected of having the virus to keep working.

Many of the other industries represented in the complaints are those deemed essential while other workplaces have been shut down, including public safety, transportation, food services and manufacturing.

Former OSHA officials say it probably investigated many complaints by phone and by asking for documents rather than conducting in-person inspections, according to the agency’s guidelines meant to minimize exposure for OSHA inspectors.

“They’re trying to call the employer up and resolve these through the phone,” said John Newquist, a former OSHA assistant regional administrator. “They’re not going outside to do these complaints because they have their own people … at risk.”

He said inspectors would ask employers about their plans, what sort of personal protective equipment they provide, whether they’re practicing social distancing and similar questions.

OSHA said it is enforcing standards for personal protective gear and sanitation as well as an overarching federal law that requires employers to “provide a workplace free of recognized hazards likely to cause death or serious physical harm.”

“Each investigation is conducted at the local level by an agency area office, and is determined on its own merits,” the agency said. “A case can be handled through an investigation or formal inspection.”

The inspection records do not detail what triggered the reviews, but relatives, companies and media accounts offer some details.

A coronavirus ‘super-spreader’

Two dozen nursing homes are under OSHA review following employee hospitalizations and deaths. One is Symphony of Joliet in Illinois, where 24 residents and two staffers died.

In a letter to Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker last week, Symphony Care Network’s CEO said administrators believe an infected maintenance worker unwittingly spread the virus at the nursing home.

“At the beginning of the crisis, in response to the orders to limit gatherings of people, a dedicated and hard-working maintenance employee set up dining tables in every Joliet patient’s room so that they would be able to take meals there instead of in our communal cafeteria setting,” CEO David Hartman wrote in the letter, which was provided to USA TODAY.

“He worked diligently and, by all accounts, exerted himself in order to serve our residents, visiting more than 40 rooms in a single day. Unfortunately, although he was asymptomatic, he was also carrying the COVID-19 virus and, through his visit to all of these rooms and his physical exertion, he was an example of … a ‘super-spreader.'”

The unnamed worker was one of two employees who died. The other was nursing assistant Sandra Green, 57, who died after struggling for 24 days on a ventilator, the Joliet Herald-News reported. Her daughters alleged there weren’t enough masks and gowns at the nursing home.

Hartman said in his letter the company has created a crisis team and has sought advice from public health experts to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. He said the company is undertaking “massive precautions” that include protective gear and screenings of staff and patients twice a day.

OSHA inspectors are reviewing workplace safety at Marion Regional Nursing Home in Hamilton, Alabama, where Rose Harrison had been a registered nurse for 30 years when COVID-19 arrived last month.

Jessica Black, Harrison’s daughter, said in an interview with USA TODAY that masks were not required and her mom wound up working for five days with a slight fever and cough. She said her mother even administered COVID-19 tests to patients and colleagues while ill.

“They told her unless she had a fever of 104 she was expected to work because she was a team leader,” Black said.

Officials with Marion Regional Medical Center did not respond to requests for comment.

Harrison was hospitalized hours after leaving work on April 3. She died three days later. “I am devastated,” Black said.

Putting their lives on the line

Research Medical Center in Kansas City, Missouri, is one of 38 hospitals that are being inspected after workers were hospitalized or died. Registered nurse Celia Yap Banago, 69, became ill after caring for a coronavirus patient in March. She died April 21, a week short of her planned retirement.

Her co-workers complained about a shortage of masks, gowns, face shields and other protective equipment. A nurses union memorialized Yap Bonago during a protest outside the White House the day after she died.

“No nurse, no health care worker, should have to put their lives, their health, and their safety at risk for the failure of hospitals and our elected leaders to provide the protection they need,” National Nurses United Executive Director Bonnie Castillo said.

Research Medical Center spokeswoman Christine Hamele said in a statement that hospital officials are heartbroken by Yap Banago’s death, have adhered to federal guidelines for protective equipment, and are cooperating with OSHA’s review.

Three medical centers run by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs are among those being inspected after worker deaths. They are in Detroit, Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Indianapolis, where three employees have died from the virus.

The American Federation of Government Employees, which represents 260,000 VA workers, has complained about shortfalls in protective gear and employee testing. It filed a complaint with OSHA in March.

Across the country, the VA says, 2,227 workers have contracted the virus and 20 have died.

VA spokeswoman Christina Noel said that’s a fraction of the workforce and a smaller proportion than other health care systems.

“We welcome OSHA oversight, but the fact is that VA’s employee safety practices have helped limit Veterans Health Administration COVID-19 employee infection rates,” she said.

‘They did not care about us’

OSHA has launched an investigation into Fayette County Public Schools in Lexington, Kentucky, where bus driver Eugenia Higgins Weathers died April 4 after contracting COVID-19.

Shacora Faulkner, Weathers’ daughter and a bus driver herself, told the Lexington Herald-Leader that bus drivers likely caught the disease in a crowded break room.

She complained that school system officials didn’t implement precautions after Gov. Andy Beshear called for social distancing, and they failed to quickly notify employees about exposure.

“Fayette County did not protect us,” Faulkner said. “Honestly, I feel like they did not care about us.”

School officials told The Courier-Journal they took precautions beginning in the latter half of March. Hand sanitizer was distributed and employees were told not to congregate in common areas.

In Arizona, OSHA is investigating a pair of rural boarding schools run by the Bureau of Indian Education after people complained they remained open amid the outbreak.

Laverne Bitsui, a longtime teacher at Rocky Ridge Boarding School near Hardrock, Arizona, died on March 23, though her family told the Navajo Times it’s unclear if she had coronavirus.

“As far as her sickness, she was sick, but we don’t know how bad,” a family spokesperson told the Times. “I think she was trying to be positive about it, trying not to get herself scared – I guess we were not expecting this. She did tell us that other employees are infected … and now they’re passing it on to their families.”

The Times reported that a staffer at Tuba City Boarding School, about an hour’s drive away, passed away two weeks later.

The Bureau of Indian Education did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Incentives to stay on the front line

OSHA is investigating a Tyson Foods meatpacking plant in Dakota City, Nebraska, where line worker Raymundo Corral died from COVID-19 on April 18. The meat-processing industry has been racked by the coronavirus.

Corral’s common-law wife, Anna Bell, told the Sioux City Journal he continued working after reporting symptoms, in part, because of an incentive program that paid $500 to workers who did not miss shifts.

“People wanted that $500,” Bell said. “I would say (to Tyson Foods), it would have been great if you would have treated your employees like human beings instead of just assets.”

Tyson Foods said in a statement that the company was “deeply saddened by the loss of a team member from our Dakota City plant and are keeping the family in our thoughts and prayers.”

“Tyson cooperates with all OSHA inspections,” the company said, but it doesn’t comment on them.

Subsidiary Tyson Fresh Meats announced Wednesday that it is pausing operations at the plant to allow for deep cleaning.