This post, Safety first: Protecting health care workers and patients, first appeared on https://www.devex.com.

Needlestick injuries, or NSIs, among health care workers remain a global burden. Accurate data is difficult to ascertain as injuries often go unreported even to this date. The World Health Organization estimated that among the 35 million health care workers worldwide, about 3 million receive percutaneous exposures to bloodborne pathogens each year; 2 million of those to hepatitis B, 0.9 million to hepatitis C, and 170,000 to HIV.

More than 90% of these infections occur in low- and middle-income countries. In other words, an estimated 40% of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections, and 2.5% of HIV infections in health care workers are attributable to occupational sharps exposures.

Unsafe injections and reuse of syringes is also a concern in the spread of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among the general population. WHO estimated that in 2010, up to 1.7 million people were infected with hepatitis B, up to 315,000 with hepatitis C virus, and as many as 33,800 with HIV through an unsafe injection.

Challenges with NSIs

“Bloodborne disease can be transmitted through unsafe sharps handling processes, and for many of these diseases, we do not have the benefit of a vaccine,” said Dr. Amber Mitchell, president and executive director of the International Safety Center, an organization that advocates for safer health care workplaces through research, surveillance, and advocacy.

The majority of NSIs occur in LMICs, many of which do not have adequate protections in place for their health workforce — from the provision of sharps injury protection devices to adequate training.

But as Ebola outbreaks in West Africa in recent years have proven, it is more important than ever to ensure health care worker safety in whatever environment they are working in.

“We don’t want health care workers to be afraid of doing their job,” said Lisa Hedman, from WHO’s Department of Essential Medicines and Health Products. “We saw that with Ebola — that medical practitioners were afraid to work. I can see why.”

For health care workers at high risk of an NSI, the potential emotional distress can have an impact on their daily work and personal lives. According to a 2013 survey, exposure to an NSI could have a severe effect on the mental health of the health care worker, leading to acute anxiety.

Obstacles in combating NSIs in LMICs

Several countries, including the U.S., EU member states, and Canada have enacted legislation regarding NSIs and safety-engineered devices. This led to widespread reductions in NSIs. For example, in the U.S., federal legislation requiring the use of safety-engineered sharp devices, along with an array of other protective measures, has led, according to recent estimates, to a 43% drop in hospitals for hypodermic NSIs.

Meanwhile, in 2010, an EU directive was published that stipulated that, by 2013, member states were obliged to implement national legislation on the prevention of sharps injuries in hospitals and the health care sector. Prior to the directive, there were 1 million NSIs recorded across Europe every year.

LMICs, however, are lagging behind.

A major driver of NSIs in LMICs is a shortage of health care workers, a lack of training on safe injections, and poor supply chain management. NSIs have a huge impact on the health care delivery system, particularly in LMICs where the workforce is already stretched thin.

“In highly overworked hospitals like AIIMS in Delhi [one of India’s busiest hospitals], patients come from all over the country and the patient-to-doctor ratio is just not up to the mark. Doctors and nurses are in a hurry,” said Dr. Sarman Singh, professor of clinical microbiology and molecular medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, who researches needlestick injuries.

Most injuries happen in the patient rooms, according to the International Safety Center, where health care workers are often under stress to perform procedures quickly. This can lead to underreporting of injuries because there is more pressure to pay attention to the care of the patient rather than self-care of the health care worker. It is another reason why the true burden of NSIs may be much higher than estimated.

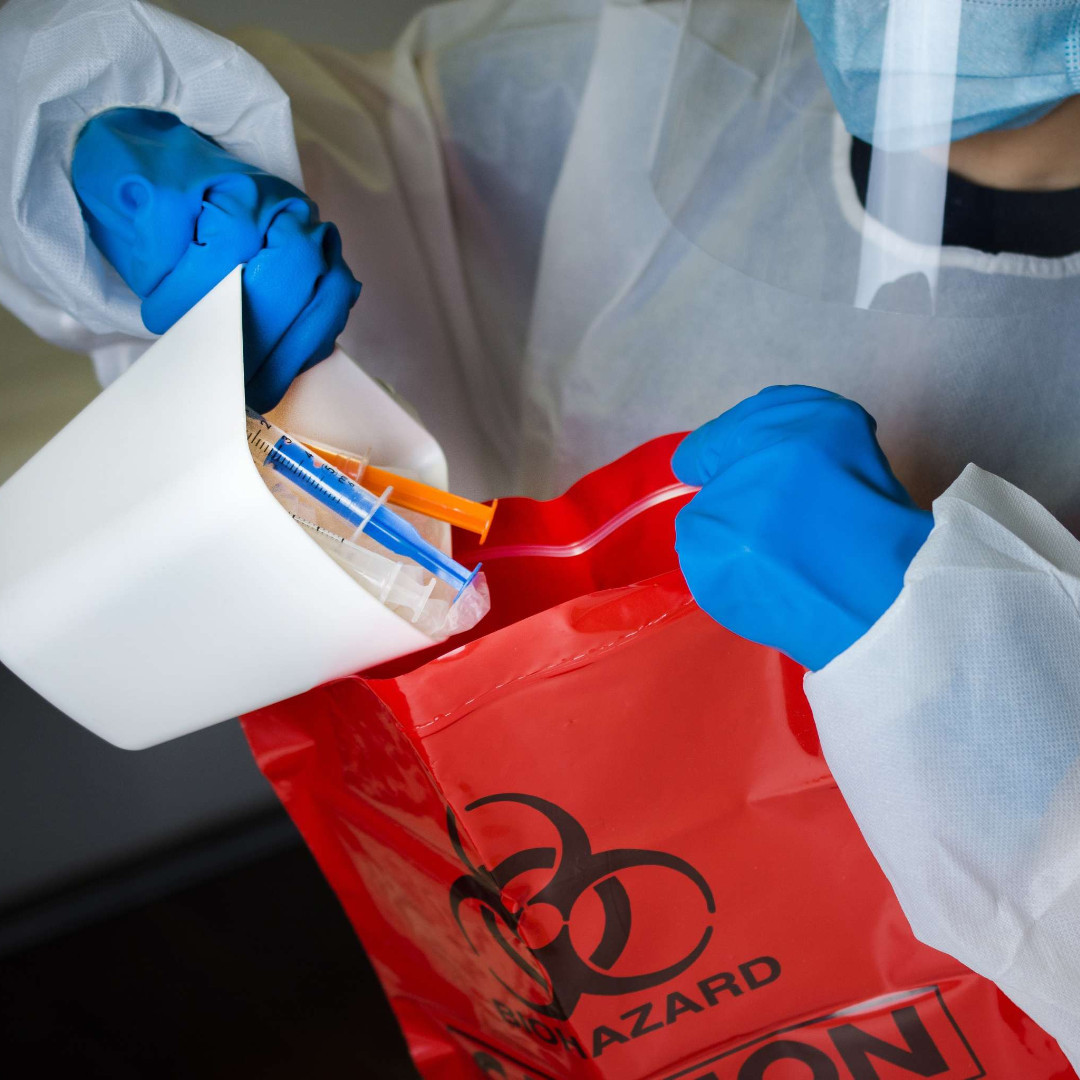

The inappropriate and improper disposal of waste is also a big driver of sharps injuries. This not only puts health care workers at risk, but research shows environmental services, laundry, and housekeeping staff — who are responsible for maintaining health care environments — are at an unacceptably high risk of such injuries.

However, NSIs for other professionals in the health care setting are also likely underreported and often it is impossible to identify the source patient, meaning that this group of professionals may have to endure longer post-exposure treatment.

“Even in countries with sharps injury surveillance systems, underreporting is a barrier to accurately estimating risk,” said ISC’s Mitchell. “The stigma associated with a needlestick or sharps injury may cause incidents to go unreported. We need to work diligently to change this culture and encourage reporting so that we can best protect health care workers.”

Even when countries have a reporting mechanism in place, there are other obstacles in getting health care workers to report injuries, either due to a lack of knowledge about the process, or fear.

“What we’ve found in a number of settings is that if you get a needlestick injury, you’re assumed to have made a mistake and people don’t want to report it,” said WHO’s Hedman, noting that another challenge is that reports lead to testing for HIV and hepatitis.

“People are afraid that if they get tested and they have contracted hepatitis or HIV, they will be blamed for it,” she said. “But if you don’t report, you don’t get post-exposure prophylaxis, or PEP. It’s not a mistake, it’s an occupational risk.”

PEP is treatment that can be used after possible exposure to a variety of bloodborne viruses such as hepatitis B and HIV. Timely access to PEP is an issue across LMICs. For example, a study conducted in Kenya between 2011-2014 found that while the majority of health care facilities surveyed — 47 out of 53 — had a 24-hour occupational PEP service in place, only half of the health facilities had access to the same services. An official ministry of health PEP register was available in less than half of the facilities studied.

But access to reporting mechanisms is not the only issue that may prevent treatment. Delays in reporting NSIs also mean that often health care workers miss out on potentially life-saving access to PEP, again driven by a lack of knowledge and a failure to report exposure, as opposed to access challenges. In India for example, according to Singh, many doctors are neither aware of PEP, nor that it should be taken as early as possible to be successful.

Solutions to address the issue of reuse and NSIs

The world has made tremendous progress toward making injections safer. In the late 1980s — driven by widespread concern that conventional disposable syringes were being frequently reused in LMICs — the first auto-disabled, or AD, syringes were designed for immunizations.

AD syringes have an internal locking mechanism that prevents the syringe from being reused once the injection is delivered. AD syringes prevent the reuse and resale of syringes and in doing so, minimize the risk of transmission of bloodborne pathogens.

In 2019, WHO and UNICEF issued a joint policy statement urging all countries to evaluate the feasibility of adopting injection devices with sharps injury protection, or SIP technologies, for vaccines.

For syringes that have a broader use beyond immunization, WHO published policy guidelines in 2015 urging countries to transition to the exclusive use of safety-engineered syringes by 2020.

WHO recommends the use of syringes with a SIP and syringes with a reuse prevention feature by health care workers delivering intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intradermal injectable medication. It also recommends the procurement of sufficient safety boxes to dispose of sharp waste safely; continuous training of health care workers on injection safety; and for manufacturers to begin or expand production of these syringes.

WHO’s guidelines, however, do not address all sharps. They are limited to injections only and do not address high-risk infusion and blood-drawing practices.

Getting LMICs to use smart syringes by 2020 is a challenge, partly because they cost more than conventional syringes.

“Price is such a huge factor in medical procurement in low-income countries,” Hedman said. “But a device alone won’t solve the problem. One thing that has to happen is training and promotion, otherwise it won’t help.”

In addition to training, Hedman added that the uptake of safety syringes would also require a fundamental change in mindset.

“We’ve done training […] and the first thing everyone would say would be: ‘Thanks for showing us these new devices, but we don’t like them because we can’t reuse them.’ A lot of hospitals and clinics in LMICs haven’t had any injection training for years. It shouldn’t be a special event like Christmas,” she said.

Mitchell agreed: “Training is a critical element to sharps injury prevention, but that doesn’t mean individual clinician behavior should be the primary focus. We have to make sure there is an institutional focus on safety, including broader uptake of safer technologies.”

While huge progress has been made in the development of safer devices, Mitchell said, there is only so far medical device innovation can go to preventing injuries and exposures.

Health care workers frequently find themselves working in high-risk environments — where there is a high prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B and C, and co-infections with multiple potential bloodborne and infectious diseases. NSIs are therefore a major concern of mounting public health importance.

Working together, the global health community can avoid the unnecessary transmission of disease through sharps. Technologies are available to prevent and reduce the issue of injection reuse and needlestick injuries, including systems for surveillance. But to truly help avert potential transmissions, appropriate guidelines need to be implemented along with a willingness to look beyond incremental cost — to safeguard the lives of health care workers and patients around the world.

This post, Safety first: Protecting health care workers and patients, first appeared on https://www.devex.com.