This post, Updates and Tips for Pharmaceutical Waste Management (Don’t Waste Time!), first appeared on http://www.pharmacypracticenews.com/.

Institutions across the country are faced with 2 key challenges related to pharmaceutical waste management: 1) the proper disposal of drugs, particularly if they are deemed hazardous, and 2) the safe and secure disposal of unused controlled substances—an effort that can contribute to the national goal of addressing the ongoing opioid epidemic. With a team approach and careful planning, both of these challenges can be met by motivated health systems.

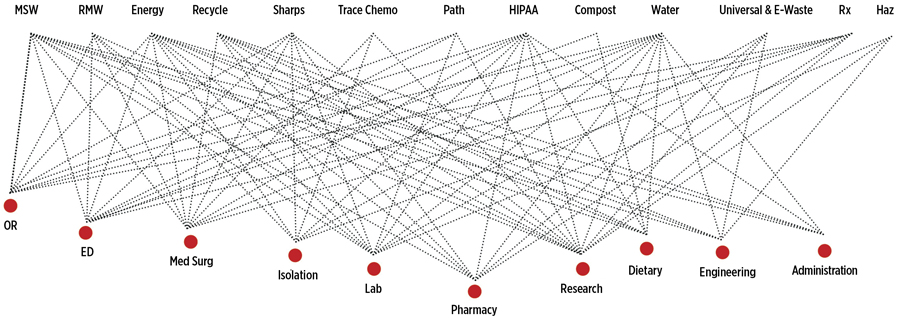

Health care providers all want what is best for their patients, employees, and the environment, but the processing of waste is chaotic and confusing, with many regulatory bodies and multiple standards that may or may not align conveniently. Additionally, waste streams within an institution are intimately connected, which can contribute to confusion about responsibility for management (Figure).1,2 Health care facilities spend more than $8 billion on energy every year and are responsible for almost 10% of the total energy used in US commercial buildings.3 A study conducted at the University of Chicago showed that the health care system accounts for approximately 8% of the carbon footprint in the United States.4 Additionally, a 2002 study by the US Geological Survey found organic waste contaminants in 80% of water streams tested.5 These numbers should be concerning to those in health care: If we heal our patients within our walls, how can we feel comfortable sending them back into a community we have contaminated because of poorly handled drug waste?

How do we best protect our employees and our patients? The purpose of this article is to inform readers about the policy and regulatory changes related to pharmaceutical waste, and how knowledge of those changes can protect patients, employees, and others.

New Environmental Standards

There are many variables that influence pharmaceutical waste regulation, and one is the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In 2015, the EPA released a proposed rule, Management Standards for Hazardous Waste Pharmaceuticals.6 The proposal was a result of the recognition that:

- patient care is health care workers’ primary responsibility; therefore, they have little time to devote to understanding the nuances of waste management;

- the continuous changes to a hospital formulary make it challenging to know which products are considered hazardous; and

- waste management involves many manual steps that are prone to human error.

The EPA also recognizes that health care facilities operate differently from industrial facilities, but both are subject to regulations on waste management under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). Prior to the EPA proposal, there was nothing specifically outlined in the RCRA for waste from any health care–related facility. In light of these points and the repeated findings that pharmaceutical waste is entering the environment, the EPA drafted the 2015 proposal to assist with appropriate management and encourage safe disposal. The EPA accepted comments on the proposal until December 24, 2015, and the public comments are still under review, with no clear timeline for implementation.7

Once the regulations are finalized, they will go into effect 6 months later. With the introduction of these regulations, the EPA anticipates preventing 6,400 tons of hazardous pharmaceutical waste from entering the environment through flushing.

What’s Considered Hazardous?

The first step in controlling hazardous pharmaceutical waste is to define what is hazardous. The guidance document by the Healthcare Environmental Resource Center, published in 2008, delineates hazardous waste into 2 categories: listed wastes and characteristic wastes.8 Listed wastes are further categorized as F, K, P, and U. Both the P and U lists contain pharmaceuticals. Nicotine, warfarin, cyclophosphamide, and daunomycin are included in these lists. In addition to P- and U-listed medications, pharmaceuticals also can be defined as hazardous if they fit at least 1 of the following measurable properties: ignitable, corrosive, reactive, or toxic when measured to determine potential to leach into a disposal environment. It is important to recognize that health care facilities are responsible for determining which substances are considered hazardous waste.6 Managing this list and appropriate disposal can become complicated, particularly when medications are given more than one designation, such as hazardous and a controlled substance, or hazardous and radioactive. Fortunately, the new EPA proposal outlines these items clearly.

A second way to define which medications are hazardous is by reviewing the hazardous drug list published by the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH), most recently updated in 2016.9 This list defines hazardous by grouping medications into 1 of 3 categories:

Group 1 consists entirely of antineoplastic agents, such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, and tamoxifen.

Group 2 medications have at least 1 hazardous drug property, such as being carcinogenic, teratogenic, or possessing potential organ toxicity. Examples include cyclosporine, fosphenytoin, and ganciclovir.

Group 3 medications such as fluconazole and warfarin primarily are associated with some reproductive risk.

Although the EPA primarily is considering hazards to the environment, NIOSH focuses much more on the safety of health care employees handling these medications and the patients receiving them. Certainly both are considerations that need to be made for the well-being and safety of everyone in our communities.

The US Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) created the USP General Chapter <800> “Hazardous Drugs—Handling in Healthcare Settings,”10 which will become enforceable in July 2018. The scope and breadth of the new chapter are significant, and the concept of waste is among the considerations institutions must discuss. The process for disposal of medications may be different from that for the “soft waste” of hazardous drug packaging and personal protective equipment. Additionally, there is human waste (excreta) of patients taking hazardous medications to consider when planning for operational changes. Development of these plans will vary by health system, and likely will require interdisciplinary conversations with nursing colleagues as well as environmental services.

NMH Green Initiative

Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) is an 894-bed academic medical center in downtown Chicago, Illinois, and recently ranked 13th on US News & World Report’s 2017-2018 Best Hospitals Honor Roll.11 In 2010, NMH developed the Green Team to promote environmental stewardship and sustainability based on review, evaluation, and implementation of waste minimization opportunities through reuse and recycling initiatives.1 The team is supported by physicians and nursing, and the operational support consists of the following members: environmental services, occupational health and employee safety, pharmacy, health care epidemiology and infection prevention, and the medical and pharmaceutical waste vendor contracted with NMH. In 2014, the NMH Green Team joined efforts with the NMHC Sustainability Committee to focus on appropriate waste management, reduction of the carbon footprint, and water conservation.

In fiscal year 2016, NMH generated more than 768,000 lb of regulated medical waste, 111,000 lb of sharps waste, and 22,000 gal of chemical waste. More specific to pharmacy, nearly 30,000 gal of pharmaceutical waste were generated during that same period (Table). NMH is striving to decrease its contribution to the carbon footprint, and it has seen some increases in its recycled materials and corresponding reductions in its trash and regulated medical waste disposal. Although not all of the changes are dramatic, this is at least partially attributed to increased understanding by staff of which materials should be deposited in which containers.

| Table. Northwestern Memorial Hospital Waste Data | ||||

| Waste Type | FY14 Generation Rate | FY15 Generation Rate | FY16 Generation Rate | FY17 Generation Rate (through July 2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated medical waste—red bag waste | 797,030 lb | 736,998 lb | 768,322 lb | 787,353 lb |

| Sharps | 106,285 lb | 103,685 lb | 111,170 lb | 111,751 lb |

| Chemical waste | 21,755 gal | 20,860 gal | 22,695 gal | 23,615 gal |

| Pharmaceutical waste | 31,410 gal | 30,531 gal | 29,597 gal | 30,359 gal |

| Plastics diverted from landfill | 126,142 lb | 115,373 lb | 120,138 lb | 116,140 lb |

| FY, fiscal year | ||||

Initiatives include streamlining waste disposal with clearly differentiated waste receptacles and significant education given to staff. On a quarterly basis, the vendor contracted with NMH performs “aftercare visits,” during which a representative from the company visits all locations in the institution where waste is generated. The representative evaluates the appropriateness of disposal and then reports back any discrepancies to supervisors for reeducation. The most recent quarterly audit of waste locations at NMH revealed that more than 70% of sites achieved a “good” compliance rating, approximately 23% achieved “moderate” compliance, and 6% were deemed noncompliant. For those areas of moderate compliance or noncompliance, notes were shared to facilitate follow-up and remedial learning for each location. Signage is posted in these areas to remind staff which waste is disposed of in which containers. There are also opportunities to use high-efficiency technology, pursue LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, and recycle materials, such as sharps containers, which can be reused up to 600 times. This recycling process is part of the way plastics are diverted from landfills (Table).

Controlling Controls

Not all waste management conversations revolve around hazardous medications. As noted, another complex component of pharmaceutical waste is controlled substance handling.

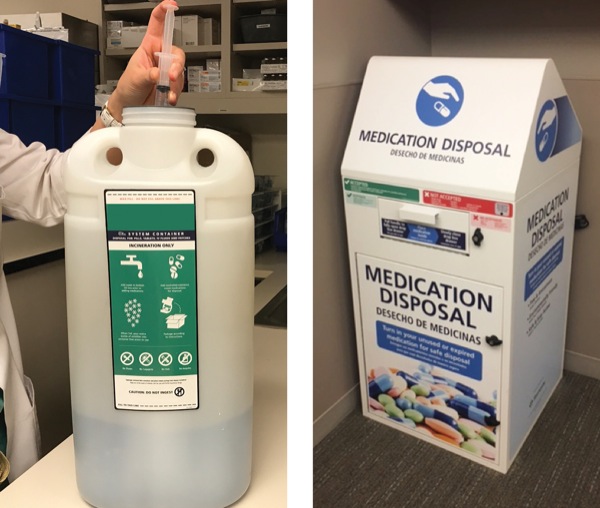

On the inpatient side, NMH uses a medication waste disposal system to render unused controlled substances unrecoverable. These types of systems reduce risk for diversion while also decreasing environmental exposure. Currently, these systems are exclusively within pharmacy locations, but expanding to the patient care units is in discussion.

On the outpatient side, NMH has been working to establish a mechanism for its patients to safely dispose of their unused medications. Pharmacists, physicians, nurses, lawyers, and the local Drug Enforcement Administration representative have all worked together to establish a drop box for unused medications within a post-op digestive health clinic. Although the program was started as an initiative to decrease excess opioid use after surgery, patients can bring any medications for disposal. NMH pharmacy manages this box in conjunction with the vendor who supplies it, and the intent is to contribute to the national goal of addressing the opioid epidemic in a safe and secure way.

There were many challenges in the rollout of this initiative, such as choosing the best location, the procedure for emptying the box, and the security required, but the interdisciplinary team championed by a physician who is passionate about public health made for a successful outcome. This initiative was particularly challenging because NMH does not have an open-door retail pharmacy in which to place the box, so the team worked to meet requirements in the clinic setting. The potential for expanding the project to other clinics in the hospital already is being discussed as the opioid crisis continues to make headlines. By decreasing the amount of unused medications that patients have and facilitating their disposal, the team hopes to reduce the amount of prescription medications circulating on the streets of Chicago.

Conclusion

Disposal of pharmaceutical waste is not necessarily among the more glamorous topics for time-strapped health systems. However, the safety of our employees, our patients, and our communities depends on the diligent efforts of every physician, nurse, and pharmacy staff member who handles these compounds.

References

- Kotis D. Secrets to a successful and sustainable pharmaceutical waste management program. Joint Commission Resources. www.jcrinc.com/?secrets-to-a-successful-and-sustainable-pharmaceutical-waste-management-program/?. 2015. Accessed September 7, 2017.

- Stericycle Inc. Interconnected waste streams. Digital image. Courtesy of Stericycle Inc.

- Risser R. Energy Department’s Hospital Energy Alliance helps partner save energy and money. US Department of Energy. http://energy.gov/?articles/?energy-department-s-hospital-energy-alliance-helps-partner-save-energy-and-money. September 4, 2012. Accessed September 7, 2017.

- Chung JW, Meltzer DO. Estimate of the carbon footprint of the US health care sector. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1970-1972.

- Buxton HT, Kolpin DW. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in U.S. streams. US Geological Survey. http://toxics.usgs.gov/?pubs/?FS-027-02/?. June 2002. Accessed September 7, 2017.

- Environmental Protection Agency. Management standards for hazardous waste pharmaceuticals. Fed Regist. www.gpo.gov/?fdsys/?pkg/?FR-2015-09-25/?pdf/?2015-23167.pdf. September 25, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2017.

- Environmental Protection Agency. Frequent questions about the management standards for hazardous waste pharmaceuticals proposed rule. www.epa.gov/?hwgenerators/?frequent-questions-about-management-standards-hazardous-waste-pharmaceuticals-proposed. August 18, 2016. Accessed September 7, 2017.

- Pines E, Smith C. Managing pharmaceutical waste: a 10-step blueprint for healthcare facilities in the United States. Healthcare Environmental Resource Center. www.hercenter.org/?hazmat/?tenstepblueprint.pdf. August 2008. Accessed September 7, 2017.

- CDC. NIOSH list of antineoplastic and other hazardous drugs in healthcare settings, 2016. Department of Health and Human Resources. www.cdc.gov/?niosh/?docs/?2016-161/?pdfs/?2016-161.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2017.

- US Pharmacopeial Convention. USP General Chapter <800> Hazardous Drugs—Handling in Healthcare Settings. www.usp.org/?compounding/?general-chapter-hazardous-drugs-handling-healthcare. Accessed August 11, 2017.

- Comarow A, Harder B. 2017-18 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and overview. US News & World Report. http://health.usnews.com/?health-care/?best-hospitals/?articles/?best-hospitals-honor-roll-and-overview. August 8, 2017. Accessed August 11, 2017.

Copyright © 2017 McMahon Publishing, 545 West 45th Street, New York, NY 10036. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form.

This post, Updates and Tips for Pharmaceutical Waste Management (Don’t Waste Time!), first appeared on http://www.pharmacypracticenews.com/.